Against Preferred Pronouns or: What Words Are For

Why we need Genesis 2 to navigate transgender language problems

What are words for?

A devilishly simple question, seemingly. But it has kept the minds of great philosophers long occupied, particularly in the last century or so. 20th century French thinker Michel Foucault once wrote: “What is so perilous, then, in the fact that people speak, and that their speech proliferates? Where is the danger in that?” He asked this with a twinkle in his eye, of course: he knew that words are dangerous things.

In the UK in 2023, few areas of language feel more dangerous to navigate than preferred pronouns.

Preferred pronouns are now, well and truly, A Thing. Even just 10 years ago, the idea that a “he” could successfully request that all the world call him “she”, on pain of reprisal, would have been baffling. But the rapid rise of transgenderism over the last decade has changed all that. Of course, other pronouns are available: they/them, ze/zey, etc.

It’s increasingly common to find preferred pronouns in email signatures and social media profiles—either because you’ve chosen something unconventional for yourself, or to show supposed allyship with those who have. It’s an issue very much in the public eye. Just recently, the singer Sam Smith (who prefers “they” to “he) has been twice “misgendered” on breakfast TV—once by an amusingly unapologetic Richard Madeley, and once by an oblivious Bob Geldof.

This is all, at the very least, fairly awkward to navigate for most people. And Christian responses to the awkwardness vary.

In the British evangelical world, there is at least a basic sense that transgenderism is, to some extent, undesirable, given the goodness of God’s design for the human body. I am glad that this much is the case (and in fact discussed this in a recent church talk on the doctrine of humanity). Yet beyond this, there seems to be little public consensus among British evangelicals about the substance or tone of a Christian response to transgenderism—either close to home at the level of pastoral care and church teaching, or further afield in the social and political arenas.

Yet there does seem to be a rough consensus from British evangelical leaders that, on balance, Christians should generally defer to using someone’s preferred pronouns. To give just one example, Sam Allberry has argued for it publicly in certain circumstances. His is, I think, one of the more thoughtful arguments (though, in all honesty, the bar is quite low). But I have seen it commended publicly in much less qualified terms than Allberry’s by a number of others, even hearing it advised in sermons at flagship evangelical churches.

What I wish to present here is one argument—and what I think is a fundamental one—for why this accommodation of preferred pronouns is profoundly, dangerously wrong, and not something Christians should do.

I say “one argument”: the reality is (and, as we will see, this all comes down to reality) that there are a whole raft of important, compelling arguments for rejecting the use of preferred pronouns in all but the most extreme circumstances. Today I offer just one.

Now, this is of course an area of immense pastoral sensitivity. People dealing with the current wave of transgenderism, and their loved ones, need deep love and compassion. I personally know trans people and others dealing with trans loved ones, so I get the stakes here.

However, a properly Christian understanding of what “love and compassion” means here is usually a far cry from what our culture thinks it means—and often a fair cry from what many Christians seem to think it means. What’s more, the evangelical tendency to belabour the sensitivity of this issue usually just leads to death by a thousand qualifications, and nothing of much substance actually being said on an increasingly urgent matter.

It is precisely because of the pastoral sensitivity of this issue that we need to think hard about principles before we are confronted with it. Without principles and theology in place, our response will always be made on the hoof, and, self-serving creatures that we are, we will be drawn to whatever response we know will make us seem compassionate—because who would want to be labelled otherwise?

So: when a Christian faces the question “should I use someone’s preferred pronouns?” they should consider a more fundamental question, the question we opened with: what are words for?

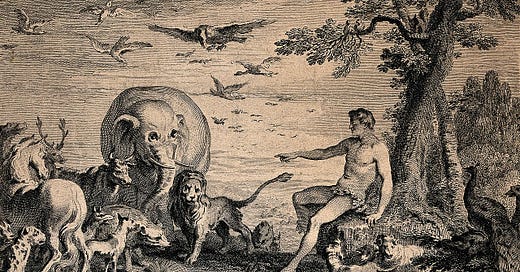

Man Gave Names to All the Animals

To find out what words are for, there is no better place to start than at the origins of human speech. Biblically speaking, we find this in Genesis 2:18-20:

Then the Lord God said, “It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him a helper fit for him.” Now out of the ground the Lord God had formed every beast of the field and every bird of the heavens and brought them to the man to see what he would call them. And whatever the man called every living creature, that was its name. The man gave names to all livestock and to the birds of the heavens and to every beast of the field. But for Adam there was not found a helper fit for him.

Adam’s naming of the animals is a hugely overlooked part of the Genesis narrative (although Bob Dylan wrote a terrible song about it). This is partly understandable, since it is largely presented as a preamble to the creation of Eve—the episode is recounted after we’re told of God’s verdict that it is not good for the man to be alone. We should recognise, then, the thrust of these verses being toward the eventual creation of Eve (though, as we shall see, that simply further strengthens the point I am going to make).

However, this does not mean we should not ask what other implications these verses might have.

Surveying biblical commentaries on the passage, three purposes are recognised in Adam’s naming of the animals.

Differentiation

The process of Adam naming the animals serves to differentiate humanity from the beasts. This is the principal way in which these verses are framed, as we have said.

Dominion

Adam’s naming of the animals in Genesis 2 reflects God’s own naming of his creation in Genesis 1, and so we should see it as an exercise of man’s rule and dominion over the earth, reflecting God’s ultimate dominion over it.

Discernment

Adam’s naming of the animals is an act of discerning something of each animal’s nature. Now, this aspect, from all that I have read, has been notably neglected by commentators, and not much discussed by those who have noted it. This seems to be because discernment is necessarily part of differentiation, and so is often folded into it: Adam must discern the nature of each animal in order to deduce their reproductive pairs, and so differentiate himself from them.

A key question arises here: is the discernment displayed in Adam’s act of naming simply in service/a part of the process of differentiation?

I do not think so. Discernment has its own importance. Let’s consider four reasons for this.

Firstly, close attention to Gen. 2:19 suggests a greater significance than mere differentiation. We are told that God brought the animals to Adam “to see what he would call them.” We are not simply told that Adam named the animals, but that God took an especial interest in seeing what he named them. Adam’s speech in itself was of interest to God, not merely his eventual conclusion of his need for a suitable helper. What’s more, we are told that Adam’s names for each animal were definitive, at least prior to the Fall: “whatever the man called every living creature, that was its name”. If the purpose of Adam’s discernment was simply to differentiate himself from the animals, retaining their names would be somewhat irrelevant after the creation of the woman: why keep the names once he had discovered his own helper?

Secondly, interpreting Adam’s naming of the animals as an act of dominion is pretty widely attested by various commentators, but has much less immediate textual support than interpreting it as an act of discernment. The dominion aspect is inferred via similarity to God’s acts of naming in Genesis 1, not by the kinds of immediate and explicit markers in 2:18-20 which we have just noted. If we accept the reality of Adam’s dominion in naming, we should be more than willing to accept the reality of discernment.

Thirdly, man’s ability to categorise animals and differentiate himself from them is something which is evident to us without Scripture telling us about it (even post-Darwin). We do not need the Bible to tell us that man is different from the animals, although it is clearly an added witness to the fact. This suggests that we are told about Adam’s naming of the animals for purposes other than differentiating ourselves from the beasts.

Fourthly, the actual names which Adam gave are lost, and so we may wonder why his naming is included at all, rather than merely his final conclusion that he was unlike the animals. John Calvin observed: “As to the names which Adam imposed, I do not doubt that each of them was founded on the best reason; but their use, with many other good things, has become obsolete.” Perhaps it was just as it’s portrayed in the Simpsons episode where Homer, imagining himself as Adam, names everything stuff like “land monster” and “tree monster.” But why record the act of naming but not the names themselves? It suggests the importance is not what Adam named the animals but that he named them.

So we are led to ask: what is the significance of naming as discernment, distinct from the process of differentiation?

Its chief significance seems to lie in the nature of language—in what our words are for.

Obliged to Name

Christian theology has long turned to the early chapters of Genesis to evidence what is often called “natural law”. In short, natural law means a rule for human conduct which is based upon God-given human nature, knowable by all men without divine revelation but simply by intuition and reasoning, and therefore obligatory for all men to follow.

Genesis makes it evident to us that there are moral truths woven into the fabric of creation which Christians can expect all human beings to know and abide by—a belief backed up in many other places in Scripture. In Genesis 4, for example, Cain needs no law to tell him murder is wrong—he knows. Or elsewhere, say Romans 1:18-31, it is clear that God expects certain forms of conduct to be evidently immoral to people aside from special revelation.

Now, we can see quite clearly how differentiation and dominion fit into natural law: in knowing our God-given human nature, we differentiate ourselves from the beasts; and the way we carry out God’s rule for human conduct is in a right dominion over creation.

So what about discernment? We asked above, “is the discernment displayed in Adam’s act of naming purely in service of the process of differentiation?” We could rephrase the question another way: is the discernment displayed in Adam’s act of naming purely part of the process of intuition and reasoning, or is it also part of the obligatory rule of human conduct?

To put it more succinctly: are we morally obliged to name things—and, more broadly, to speak about them—rightly?

It seems evident that yes, we are.

To name or speak of something is to have a “copy” of it in one’s mind, as a distinct object—to internally recognise something as a distinct entity. This is the act of discernment which allows us to differentiate. The two acts, as we have said, necessarily go hand in hand, and yet we can regard them as distinct. To discern X with your mind is not merely to recognise it as simply not-Y. It is also to positively recognise it as X.

To steal an example from the Genesis commentary of the theologian Gerhard von Rad:

“Concretely: when man says “ox” he has not simply discovered the word “ox,” but rather understood this creature as ox, i.e. included it in his imagination and his life as a help to his life” (emphasis added).

This is what took place when Adam named the animals: a positive discernment of each thing as itself, not simply as not-another. The two cannot be separated, but they can be distinguished.

Now, perhaps we might agree that this is an accurate description of what goes on in human language. But can we say that it is part of the natural law—something we are naturally obliged to do, and something we can expect all men to understand?

I believe so, and I’ll give three reasons.

Firstly, and most briefly: the Christian natural law tradition broadly regards all the ethical conclusions deductible from Genesis 1-2 as part of natural law. Therefore, there seems to be little remit to exclude an obligation for accurate speech.

Secondly, accurate speech is already an assumed part of other well-established parts of natural law theology. For example: natural law is something knowable to all people, but human beings never know things without using language. We know by naming. The same is true of our obligation and ability to create and enforce specific laws which are in accord with natural law: laws cannot be made and promoted without language. So questions of knowledge and forming just laws are, considered one way, merely forms of our ability and obligation to speak rightly about reality.

Thirdly, as should be expected with natural law, we can see this sense of an obligation to correctly name things evidenced in human history and society. Ethical disagreements almost always involve fevered disputes over terminology, which are taken to have a significant bearing upon the nature and direction of the disagreement.

To dispassionately consider one well-established example, consider the “pro-life” v. “pro-choice” framing of abortion debates. Both sides have taken care to name their own position as “pro” rather than “anti”, and to relate it to something positive with which no reasonable person could, presumably, take issue: no-one wants to be known as “anti-life” or “anti-choice”, or even “pro-restriction” or “pro-abortion”. Both sides see their terminology as speaking of some fundamental truth of human nature. Similarly, what one side calls “abortion”, the other calls “murder”; what one calls “an unborn child”, the other calls “a clump of cells.” Everyone involved thinks these distinctions matter, so it is evident that people feel that right speech—speech that reflects reality—is an ethical obligation.

From Discernment to Declaration

We’ve asked “what are words for?” Usually, when we Christians consider this question, our considerations are fairly limited. Unethical speech is usually considered to consist of (i) intentionally lying or deceiving, and/or (ii) causing offence or upset.

Yet what we have seen above must push us further than this. At the genesis of human language, we see a high calling upon Adam’s speech, a calling which God delights to see him carry out: to speak in a way that honours and reflects God-given reality.

And we see this all the more gloriously in the first human speech that is actually recorded, Adam’s song to Eve in Genesis 2:23:

The man said,

“This is now bone of my bones

and flesh of my flesh;

she shall be called ‘woman,’

for she was taken out of man.”

What do we see here? Both differentiation and discernment! Adam sees that Eve is like him—bone of his bone, flesh of his flesh. Yet she is also unlike him—he is man, she is woman; in Hebrew, he is ish, she is ishah. This is more than a mere negative declaration, more than saying Eve is simply “a Not-Man”. It is a positive declaration: she is a woman. And Adam cannot but bubble over in speech about this, speech that must be reflective of this God-given reality which he receives as a gift. Discernment becomes declaration.

And we should note: Eve does not identify herself to Adam. Adam sees, knows, and names.

So, how does all this relate to preferred pronouns?

If our sole considerations for ethical speech are avoiding intentional deceit and offence, then adopting someone’s preferred pronouns seems inevitable.

However, if we have an obligation to speak rightly of something based upon the reality of what it is, then we have a different, very important consideration to make. The origins of language lie in making a right declaration about something, having discerned what it is. This consideration precedes any others we might make about offence or upset.

Preferred pronouns are a rejection of God’s purpose for our words. They deny what our minds can clearly discern: the good existence of male and female. They shun the obligation we have to declare what we have discerned. And so they are unethical and unacceptable speech for anyone—let alone Christians.

Now, as noted at the start, I will concede very extreme circumstances in which one might, temporarily and contingently, use preferred pronouns—say, if a mentally unstable man were holding a gun to his head right there and then, and threatening to pull the trigger if you don’t call him “she”. At this point, all language has dissolved into nonsense—it is a situation essentially the same as playing along with the delusion of an elderly person suffering dementia, or with a child absorbed in a roleplaying game.

The move that the trans movement tends to make at this point though is to say that, in effect, trans people constantly have a gun held to their own heads, and that if we don’t affirm their pronouns then their blood will be on our hands. As the line goes, “would you rather have a living son or a dead daughter?” This, however, is a scandalously manipulative premise which Christians should utterly reject—it is this premise which has pressured thousands of (still culpable) parents into affirming their children into gender transitions which will wreck them for life and which they will one day regret. A lifetime of living in a trans identity—especially the highly spurious kind of trans “identity” which has rapidly arisen in the past decade—is not the same thing as an acute moment of psychological breakdown, and they should not be responded to in the same way or with the same kinds of speech.

C.S. Lewis famously wrote about how an enjoyment of something is not sufficiently complete until it is praised:

“I think we delight to praise what we enjoy because the praise not merely expresses but completes the enjoyment; it is its appointed consummation. It is not out of compliment that lovers keep on telling one another how beautiful they are; the delight is incomplete till it is expressed. It is frustrating to have discovered a new author and not to be able to tell anyone how good he is; to come suddenly, at the turn of the road, upon some mountain valley of unexpected grandeur and then to have to keep silent because the people with you care for it no more than for a tin can in the ditch; to hear a good joke and find no one to share it with.”

We could say the same thing about naming: we delight to name what we enjoy because the naming not merely expresses but completes the enjoyment. Like praise, correct naming cannot help but bubble up from within us. It begins with recognising a distinct reality, but then erupts by necessity in audible speech. This is why Adam named the animals, even though there was no one else to hear him but God, who knew Adam’s words even before they were on his lips. It is why Adam erupted in song upon the arrival of Eve. He was never told to name the animals, or the woman. God brought the animals to him to see what he would name them, and presented the woman before him, and Adam could not help but name them.

Like the rest of the natural law, the need to name things rightly is written upon our hearts. All mankind, therefore, is obliged to keep it upon its lips—and Christians especially so.

This post is the fourth and final free, public post launching The New Albion in March 2023. If you have benefited from what you’ve read, then support me to keep writing by taking out a paid subscription.

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

This is truly a wonderful posting. It follows the same tracks as my work on the subject. A theology of language is entirely crucial for proper Christian theology.

A. B. Caneday

Christ Over All (https:christoverall.com)