Christianity and Transgenderism: A Youth Group Session

A free public post on teaching 14-18s about the hottest of topics

Over the summer term this year, we took our church 14-18s youth group through a series we called “The Good News About Men and Women”.

Every Friday night, we get around 50 teenagers at church, a good mixture of Christians and non-Christians. The aim of this series was to facilitate discussion of the vexed questions of sex and gender—something which, by their own admission, is forbidden at school. After a good amount of discussion, we’d then present an initial Christian response to the topic at hand.

We started off with “Men and Women: An Introduction”, giving a brief sketch of the biblical and natural design for men and women. Then, we specifically looked at Christianity’s good news for women, and then its good news for men.

With that groundwork in place, I then led a session on transgenderism. Below is the content of that session, lightly adapted to make it suitable for reading. I share it in the hope that it might prove useful to others who are wondering how they can approach this issue with the young people in their lives.

Admittedly, we are fortunate to have a well-behaved youth group, where even the non-Christians are usually keen to engage, or at least willing to sit and listen, and so the below may seem like a heavy session. It may not be directly transferrable to your context, so adapt and borrow as you please.

But let me say: don’t underestimate teenagers’ willingness to engage on this topic at length. The session confirmed my suspicion that most teenagers, whilst highly permissive of transgenderism, are not at all actually convinced by it.

The first half of the session was more discussion based, involving some video clips, linked below. The second half is then my attempt to present the most important elements of the Christian response to the issue at large and some of its most pressing practical questions.

Most of the stats quoted below come from Abigail Shrier’s excellent book Irreversible Damage: Teenage Girls and the Transgender Craze (2020).

So, having established a biblical view of men and women, we come now to transgenderism. A sensitive and controversial topic—but perhaps the thing, more than anything else, which makes questions about men and women a hot topic right now.

Now, let’s bee clear: our aim here is not for us as a church or as Christians to shove stuff down your throats. That’s why we’ve planned this whole series like we have—in a seminar style with more discussion time rather than just a straight talk from the front.

I’ve been really impressed over the last few weeks with everyone’s willingness to discuss, to be open, to let others speak, to disagree. After the first session, some of us got into a conversation about men, women, and transgenderism, which I thought was a real model of how to discuss this. One of you said “if we had this conversation in the common room at school… there would be no conversation, everyone would just agree!” So it seems you need to come to church now to have the controversial discussions!

But, as ever, our aim is to present a brief outline of the Christian response to this issue. There will be a million and one things about this that we could discuss, but we don’t have time to do it all, so I want us to consider just a few main points.

And it should be said here, as has been said every week, that we know this is not just an abstract issue. You guys will already, even at your age, have experienced some of the hard things about being young men and young women, or you are close to people who have among your friends and family. Some, maybe most of you, will have friends or at least know people at school or elsewhere who identify as “transgender”. I do—I have two trans people in my family. So I know that this is a very real thing, involving real people, with real lives—people who, let me say unambiguously, I firmly believe God loves, and who I believe Jesus died for, and whose greatest need is to believe in him and have their sins forgiven, the same as I believe about any of you.

So, let’s ask: what is transgenderism?

A definition, taken from the writer Kathleen Stock:

You and I, and everyone else, have an important inner state called a gender identity

For some people, inner gender identity fails to match the biological sex—male or female—originally assigned to them at birth by medics. These are trans people.

Gender identity, not biological sex, is what makes you a man or a woman (or neither).

The existence of trans people generates a moral obligation upon all of us to recognise and legally protect gender identity and not biological sex

This, I think, is what people generally mean when they talk about “transgenderism” these days.

Now, that’s all bit technical, so let’s illustrate. Watch the clip below, from 00:00-02:50:

Having watched that, answer these questions:

In the clip, what determines whether Jazz is a boy or a girl? What assumptions do people have about the relationship a person has with their body?

What things convince others that Jazz is a girl?

What role do adults play in Jazz’s transition?

So now, we’ve hopefully got a sense of what we mean when we say “transgenderism”.

When Christians encounter this, what sort of things determine their response? Well, I think we can break it down into four main principles.

1. The body is good

Take a look at the following Bible passages, and ask “what do these verses tell us about the human body?”

Genesis 2:7:

Then the Lord God formed a man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living being.

Genesis 2:21-23:

So the Lord God caused the man to fall into a deep sleep; and while he was sleeping, he took one of the man’s ribs[g] and then closed up the place with flesh. Then the Lord God made a woman from the rib[h] he had taken out of the man, and he brought her to the man.

The man said,

“This is now bone of my bones

and flesh of my flesh;

she shall be called ‘woman,’

for she was taken out of man.”

John 1:14

The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the one and only Son, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth.

John 20:19-20

On the evening of that first day of the week, when the disciples were together, with the doors locked for fear of the Jewish leaders, Jesus came and stood among them and said, “Peace be with you!” After he said this, he showed them his hands and side. The disciples were overjoyed when they saw the Lord.

Phil. 3:20-21

But our citizenship is in heaven. And we eagerly await a Saviour from there, the Lord Jesus Christ, who, by the power that enables him to bring everything under his control, will transform our lowly bodies so that they will be like his glorious body.

In all these verses, we see that, in the Bible’s view, the human body is good.

Gen. 2:7 - God reaches into the dust and forms Adam’s male body, breathing live into it. He does this with no other creature; he merely speaks when he makes them

Gen. 2:21-23 - similarly, Eve is lovingly crafted, made from Adam’s flesh; what’s more, their bodies complement and relate to one another, and become “one” again in marriage

John 1:14 - Jesus, the Word, became flesh and took on a human body. God treasures and values human bodies, so much so that he is by no means above taking one on himself.

John 20:19-20 - when Jesus is raised from the dead, it is in a body—he doesn’t float off to heaven just in his soul; no, resurrection means a real, perfected physical body

Phil. 3:20-21 - because Jesus has a perfected resurrection body, so too will Christians; we won't float off to Heaven in a cloud, but will have bodies forever—the bodies God gave us at birth, but perfected

Back in Week 1, we said that men and women are basic and binary.

Basic because the distinction between men and women is, in Genesis, as important as the distinction between light and dark, day and night, land and sea. It is fundamental to who we are—the first thing you notice about someone when they walk into a room is if they’re male or female.

And we are binary, meaning “twofold”, because we are different and complementary. Men and women have unique strengths and struggles that complement each other.

And that is good! After he made everything else in creation, God saw it was “good”; after he made man and woman, in their bodies, he said “it’s very good.”

So our bodies, although they are fallen and not perfect, are basically good. Human beings are more than their bodies—we are made in God’s image, and so have a soul. But we are not less than our bodies. We don’t experience life other than in our bodies.

So, although there is such a thing as “gender” as distinct from “sex”, the Bible should lead Christians to reject the idea that everyone has a unique, internal “gender identity” which can be at odds with your body.

Gender, rather, is how the reality of our maleness or femaleness, which is determined by our bodies, gets played out. If your bodily sex is the sheet music, your gender is the performance of it.

Now, you can have different kinds of men and different kinds of women—more “feminine” men, more “masculine” women. But, because Christians believe in the goodness of the body, made by God, they can’t accept that gender and sex are really separable.

And again: all this is good news—because it means that there is not a burden on us to “discover our gender identity”. Doing so is an exhausting process—and what if you get it wrong? But if the body is good, you don’t need to go looking for who you are— you just need to grow up into it.

2. God is compassionate

Now, having said all that: what about the reality of transgenderism?

Even though I say all this about the body being good, a growing number of people, especially young people, don’t feel the body is good. Rather, they feel it’s bad, that they’re in the wrong body. They experience what we now call “gender dysphoria”—feeling that their gender does not match their sex.

And I am not denying that that is something many people now experience. People often want to describe pushback against transgenderism as “erasing trans people” or “denying their existence”. I am not denying their existence; I just deny the premises of how they explain the difficulties they have; I don’t deny that they have those difficulties.

I think here, it would be really helpful to watch a short clip of someone talking about their difficulties. Watch this video from 03:34-04:54:

Now having watched that clip, discuss these questions:

What words does Page use to describe the experience of gender dysphoria?

What things triggered Page’s difficulties?

How did Page want to feel instead?

So, this is an incredibly hard story. And let me say: God has immense compassion on this whole situation. In the Christian view, this is not how it should be. God made us, and made our bodies, and it is tragic that anyone should be so in pain that they feel they’re in the wrong one. That, for Christians, is a result of the Fall—it’s not how God intended things to be.

I could pile up Bible verses on God’s compassion for people who are weak, sick, distressed, weary, in pain. Here’s just one: “When [Jesus] saw the crowds, he had compassion on them, because they were harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd” (Matthew 9:36)

That sounds like a good description of how Ellen Page was feeling for many years—and probably still feels. “Compassion” means “to suffer with”, and Jesus, we know, has suffered greatly. So he has true compassion on anyone who experiences the pain of gender dysphoria.

And that, for Christians, means that Christians need to have compassion on people who suffer with this.

But the question is: what, in this hard, hard situation, does compassion look like?

3. Truth is loving

To respond in a truly compassionate way, we need to know what the truth is.

And everyone agrees with that. What we hear most of the time is that the truth is that a trans person really is in the wrong body, because they really do have a gender identity that really does not match their sex. And so we need to affirm that truth and help them to live in light of it—by changing their pronouns, their name, their clothes, by taking hormones, even by having surgery.

From what we’ve seen so far though, the Christian response is different—indeed, it’s even a response you don’t have to be a Christian to share. The truth is that our bodies are good, and they determine who we are.

And I am convinced that looking closer and closer at the facts about modern transgenderism actually bears that out, and that you don’t even really need the Bible to tell you a lot of this. The Bible just confirms what is evident when we look at the facts.

I think it’s really important here to talk about some facts about “transgenderism” as we experience it today. As has already been touched on, in schools now, there is basically no room for discussion about transgenderism—it is taken as established fact.

But the way it is often presented to us actually obscures the truth about where transgenderism as we know it comes from.

A History of Transgenderism

I think we need to distinguish between transgenderism as it’s been understood by doctors and psychologists for the past 70 years or so, and transgenderism as it’s been understood for only the last 10 years or so by the wider culture.

Since around the end of WW2, doctors and psychologists began to study a tiny fraction of the population who experienced some very, very rare conditions—either people who were intersex (i.e. their sex is unclear); or people who experienced gender dysphoria (i.e. feeling that their body did not match their gender). These conditions, for decades, have been vanishingly rare. Gender dysphoria, as diagnosed by a medical professional, was expected to occur in fewer than 1 in 10,000 people. So, in the UK, with a population of 67 million, we should expect around 6700 people to have gender dysphoria.

Now, most people in this category have a genuine medical or psychological condition, just as some people are born with other medical problems, or born prone to things like depression. This is tragic and painful, and a result of the Fall. And I would hesitate hugely before offering any opinion or judgement on how you help people in those situations.

But these genuine medical conditions are, by and large, not what people mean when they talk about transgenderism now. In the last 10 years or so, for various reasons, we’ve seen the rise of what many now call “rapid onset gender dysphoria”.

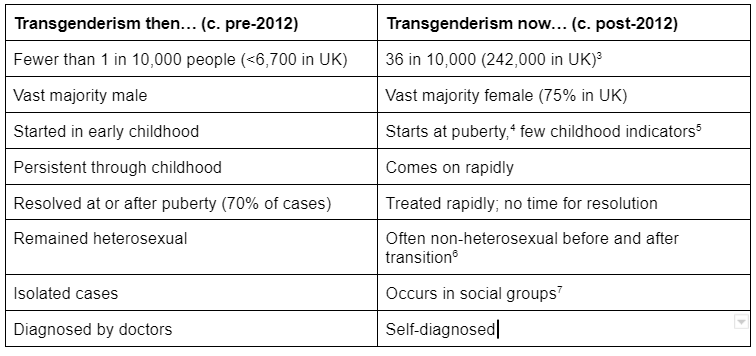

Let’s compare what I call “transgenderism then” (roughly pre-2012) and “transgenderism now” (roughly post-2012—interestingly, the year in which smartphone use became truly widespread):

See the massive changes here. See that increase—36 times more, or an increase of 3600% percent. Similarly, in the UK, in the last decade, the percentage of children referred for gender transition treatment has increased 4000%.

It used to be almost exclusively a male problem. Before 2012, there was no scientific literature of gender dysphoria in girls aged 11-21 - because it did not exist. Now, the vast majority of people identifying themselves as gender dysphoric are girls - ¾ in the UK.

There are other factors too. Transgenderism now has a very high correlation with high-functioning autism. Over 90% of trans people are white. The vast-majority come from what could comfortably be called middle or upper class backgrounds. Over 65% had spent increased time on social media before coming out as trans—the rest, presumably, were on it virtually all the time anyway.

This is the kind of transgenderism you guys are faced with in school. It is not the genuine, incredibly sad medical or psychological condition that doctors have been aware of for about 70 years. And it’s not what our culture, or your school, tell you it is (i.e. helping people realise who they really are).

Now, the argument might be that now people are just more aware of the possibility of being trans, and feel able and happy to “come out” and embrace that. But the stats here just do not back that up.

All the indicators are that transgenderism as we know it is a social phenomenon, driven by social pressures and access to the smartphones, largely occurring among young girls who are unhappy with themselves. It is incredibly similar to the rise of eating disorders in the 1970s, and the rise of self-harm in the early 2000s.

We’ve seen these last two weeks: being a young man or young woman is incredibly hard in the world today. Men are anxious to distance themselves from any kind of “masculinity” because they fear being labelled with “toxic masculinity”—and there’s no better way to get away from that than by becoming a woman. Girls are over-sexualised, with men constantly looking at them, and boys, who’ve learnt everything they know about sex from watching porn on their phone, treating them badly. So perhaps the best way to escape the problems caused by your feminine body is to turn it into a gender-neutral or masculine one.

Gender transition presents itself as a kind of Gospel, a kind of good news for people who really are in pain. It says “if you change this, then you’ll be happy with yourself.” And so people change their name, behaviour, pronouns, how they dress. An increasing number are taking hormonal drugs and undergoing irreversible surgeries to change their bodies.

But there is a growing number of people who regret identifying as trans and undergoing treatment—“destransitioners”, they’re called. 41% of trans-identifying people attempt suicide at some point, and transitioning does not lower that statistic—it may even increase it, studies show.

And if what we said at the start is true—that our bodies are good, that they are inseparable from who we are, that it is good for us to accept them and grow up as men and women—then it makes sense that gender transitions are proving not to make people happy.

And so, when it comes to the compassionate Christian response to transgenderism, that means being honest about these facts, and acting accordingly.

It means not affirming someone’s gender transition, because you can see that, in all likelihood, they have been swept into something which is offering to solve their problems, but in the end will just leave them even more damaged than before—and in irreversible ways, especially if they’ve been on drugs or had surgery.

There are bad ways to go about sharing the truth in love. As we’ve said: these people really are in pain, and really do need love and compassion. We shouldn’t go in all guns blazing. We should be gentle and kind and patient—but ultimately firm.

Everyone agrees that the most loving thing is for someone struggling with their gender to live in line with the truth. And the stats increasingly back up the biblical view as being true: that our bodies are good, and are part of who we are.

4. Society needs protecting

One of the big things that makes transgenderism such a contentious issue is question of how it affects wider society.

We might concede that, if someone wants to, they can identify as a woman or a man—surely it doesn’t hurt anybody else?

But we’re beginning to realise it’s not that simple. When trans people insist on other people using their new names or new pronouns (e.g. calling them “he” or “they” instead of “she”), that effects others. Should you use their pronouns? If you don’t want to, should you be made to?

Or, when trans people want access to things usually reserved for people of the same sex—e.g. Women’s sport, or women’s changing rooms—that effects the women who use those spaces (e.g. Lia Thomas (born William Thomas), the man who has dominated female swimming competitions, or Isla Bryson (born Adam Graham), the convicted rapist put into a woman’s prison).

We all agree that society needs protecting. But what principles should direct how Christians see the protection of society? I have two to think about briefly:

God made us into a society, not just individuals

Consider this verse:

“From one man [God] made all the nations, that they should inhabit the whole earth; and he marked out their appointed times in history and the boundaries of their lands” (Acts 17:26)

Societies only work because we place the good of everybody over the wishes of the individual.

We have a duty to protect things which we share in common. For example, we protect public spaces, parks etc. because others use them, and will continue to use them after we’ve gone. If we let individuals do whatever they want to those shared public things, society would soon break down.

And when trans people make demands that others must use their new names or pronouns, or to use single-sex spaces, they are demanding that their individual wishes trump the rest of society. And, although Christians value every individual as made in God’s image, we also value the fact that God has made us not just as individuals but as societies. So individual wishes do not always win.

As well as preserving public things like public spaces, public facilities, public services, it’s also our duty to protect public ideas and public culture. That includes some shared public idea of what it means to be a man or a woman—we should want a society, whether we’re Christian or not, in which young men and women can grow up to thrive as men and women.

And so when it comes to questions of, for example, using someone’s preferred pronouns, I think the Christian response really should be to say “no” in the vast majority of cases.

There are numerous reasons, but a big one is that, if we concede the basics of our language out of apparent compassion for an individual, we gradually chip away at our shared public idea of what men and women are. Christians are meant to love their neighbours—it may seem loving to your trans neighbour to use their preferred pronouns, but it fails to love all your other neighbours, because you are chipping away at something we have in common and need to preserve for the good of all.

Other Christians would disagree with me in good faith on that, but I think the argument stands, and there are other good arguments against preferred pronouns, and other such things.

Societies must defend the most vulnerable

Consider this verse:

“Defend the weak and the fatherless; uphold the cause of the poor and the oppressed” (Psalm 82:3)

Societies are meant to protect the weakest and most vulnerable. This is a basic social principle on which basically everyone agrees with now—and we only agree on it because Christianity has had such an influence on our society! Ancient Romans, for instance, did not think you needed to protect the vulnerable.

There are three relevant vulnerable groups when it comes to the issue of transgenderism:

Trans people

Women

Children

Now, “protecting the vulnerable” is often the argument used for why we should embrace transgenderism. We are told that trans people are a sexual minority, are bullied, attacked etc. and thus society needs to marshal all its resources in their service.

And, again, Christians must concede: most trans people certainly are very vulnerable and distressed, and need help—just not in the way that most people think.

But, in view of what we’ve seen—that the body is good, and that modern transgenderism is a social phenomenon that actually damages vulnerable young people—defending vulnerable trans people ultimately means helping them to learn to accept their bodies, not affirming their gender identity.

Women, as we’ve seen in this series, are also more vulnerable than men in society. And the push for “trans-women” (i.e. men) to enter into women’s spaces is dangerous to women. Just yesterday there was a new story that in Essex, girls are being assaulted by boys in gender-neutral toilets. To the girls here: there is no reason this couldn’t happen at your school. Protecting the vulnerable means protecting women’s spaces.

And children, too, are vulnerable, in part because they are so suggestible. We saw Jazz Jennings (who was born Jared) at the start—he began transitioning when he was 4, just because he liked girly things. As the earlier stats showed, even though his mum said “it was not a phase”, he would likely have grown out of it. My son’s favourite game right now is pretending he’s a mummy rabbit who’s got babies in her tummy. Increasingly, the trans movement would want me to say to him “well maybe you are a mummy! Do you want to be a girl?” And they’d want me to start his gender transition now—which would be an evil thing. Protecting the vulnerable means protecting children.

Conclusion

So, we’ve covered a lot. Let’s recap the main principles which should direct the Christian response to transgenderism:

The body is good

God is compassionate

Truth is loving

Society needs protecting

Now, as we end, let’s remember: we called this series “The Good News About Men and Women.” And we really do think that it is good news to tell people that, actually, God made you in his image as a man or a woman. We think it’s good news to say that, actually, you don’t need to discover your unique gender identity—because that is exhausting! What a burden to put on people. And what if you get it wrong?

As I’ve said repeatedly: people who end up identifying as trans do so out of deep distress, and deep confusion about their identity. And we can get why they feel driven to it.

But the only thing that really provides the secure, unshakeable identity that all of us—trans or not—are looking for is Jesus. He is the one who created us in the first place, and he’s the one who can save us from the mess we make of our lives.

Whoever you are, and whatever struggles you’ve had with sex and gender, let me tell you that Jesus is ready to welcome you, even if you’re still full of questions. And you might not like all his answers—but they are good, loving, and full of life.

Well done for deaing with this in YPF. The PC version of this, where no-one is allowed to give offence, hides all those eye-opening stats and the alternative view of what compassion should consist of. It would be interesting to know what the considered response of the young people has been.