Raise Against the Machine #1: The Millennial Parenting Moment

A new ongoing series on Christian parenting in the digital age

This post is the first in what will be an ongoing series about parenting in the digital age, which I’m calling “Raise Against the Machine.”

I have dithered a great deal over whether to start writing regularly about parenting here at The New Albion, for a couple of reasons.

First, I am, on a daily basis, made aware of my shortcomings as a father. Morally speaking, who am I to be writing publicly about parenting?

Second, my children are not yet grown. At the time of writing, they are 5, 3, and nine months old. Have I really got much to say, having not yet gone the distance with any of them? One of the paradoxes with parenting is that by the time you feel you’ve become adept at parenting a five year old girl, you suddenly find you have a six year old girl and that you have a whole new load of things to learn. Further, offering parenting advice when your kids are still young all too swiftly turns into lecturing your peers about how they should raise their kids of the same age—something guaranteed to end badly.

Yet I have been encouraged to write about this by others, and so here I am. As should be clear, I am not offering the advice of a seasoned pro. Yet, if everyone waited until all their children were well-adjusted adults before weighing in on parenting, very little advice would ever get given—and a lot of it would be out of date, especially in an era as rapidly changing as our own.

To break down my chosen title:

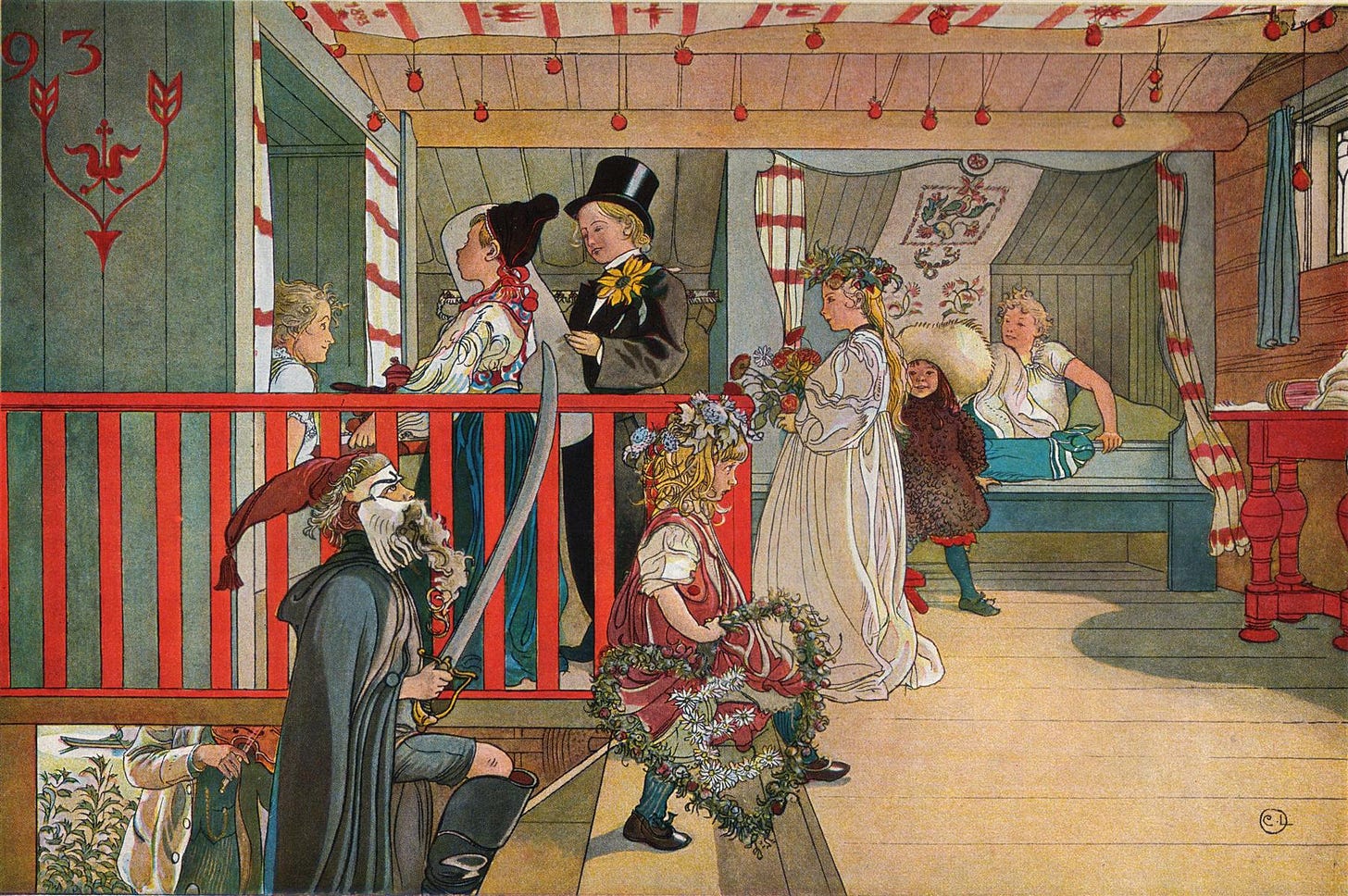

Raise: I want this to be a positive project. Few things, parenting least of all, can sustain themselves in a healthy way if they are only defined by what they are against (though I am partial to books and essays titled things like “Against XYZ”). Everything becomes reactive and bitter. We cannot just pull away or attack things; we must raise our children up toward something positive—a positive vision of a rich, fully-rounded human life rooted in the triune God and his creation. Call me a hapless romantic if you will, but it’s a vision I’m often inspired by in the paintings of Carl Larsson, like the one pictured above: a family home full of celebration.

Against the Machine: all that said, the fact is that parenting in the digital age is beset by an unprecedented set of challenges which require us to know what we are against. Indeed, if you are for some things, you will necessarily be against their contraries. We must know our enemies, even if we must avoid being defined by them. I have found describing these enemies under the category of “The Machine” to be very helpful in recent years. I’ll explore The Machine in later posts, but I first took the term from Paul Kingsnorth, who himself took it from writers like R.S. Thomas, Dylan Thomas, E.M. Forster, and Lewis Mumford (I wrote about Kingsnorth for Mere Orthodoxy a while back if you’re interested)

The aim is for this to be a “here and now” exploration of faithful Christian parenting in the digital age. It will not be a systematic manifesto, since I have no such thing. Rather, it will be notes and reflections from my own thinking and parenting as it unfolds, with due discretion given to my children’s privacy.

This will by no means be a foolproof guide. Indeed, such a thing simply cannot exist right now, because no one has ever parented through the digital age before. Children born the same year as the iPhone only turn 17 this year. Which takes me to my main thought in this first article: the unique opportunity currently open to Millennial parents.

The Millennial Parenting Moment

One distinction sometimes made between Millennials and Gen Z is that the former are digital natives whilst the latter are digital junkies. Yet this isn’t quite right. To be “native” is to be born into something—but Millennials weren’t born into the digital age. We were born between 1981 and 1996, and so the youngest were 11 by the time the iPhone came out. Our childhoods, then, were largely offline—or at least, significantly more so than Gen Z after us.

I was born in 1992. I remember dial-up. I remember AOL. I remember cassette tapes. I remember house phones. Admittedly, my childhood did involve too much time on screens indoors, but this was largely playing offline video games. My early years of secondary school also involved a lot of MSN Messenger and Bebo, but without a smartphone these didn’t follow me wherever I went.

Although Millennials are digitally fluent, I don’t think we are truly digital natives. I think that many of us can actually recall the transformative effect the digital world had on us when it arrived. I ruminate often at the minute on something my wife said after we got rid of our TV, which I recorded in my recent piece on the subject:

I love not having a TV. It’s like I’ve got my brain back. I feel like I’ve not had this brain since before I got a smartphone. It’s like it’s got its shape back. I actually want to spend the afternoon painting or something—that’s always what I did when I was a teenager. I always thought it was a mental health thing—but maybe it’s just been my phone.

I think most Millennials can recollect a similar experience—a time, probably during our teens, where it felt like we lost something: the ability to concentrate, to read a long book, to busy ourselves with our hands or a creative pursuit. We know we could do it once, but can do so no longer. We remember our brains losing their shape.

By and large, however, Gen Z never had this. The iPhone came out before they’d even finished primary school, and was ubiquitous before they’d started their GCSEs. They are the first real digital natives, and cannot imagine a world in which they are not constantly online. Their brains never had the chance to take on a shape in the first place.

What about the older generations though—the Baby Boomers and Gen X? We all know, of course, that middle aged and older people can be addicted to their phones like the rest of us. But, in short, these older generations simply don’t appreciate the nature and scale of damage done to the brains of their Millennial and Gen Z children and grandchildren.

Millennials, then, straddle the divide between the pre- and post-digital. We’re aware of what’s been lost and so what might be regained, as well as appreciative of the genuine benefits the digital age can offer.

And so I think we are in a unique window where Millennials can set the tone on Christian parenting for the digital age. We’re aged between 43 and 28, and so most young children today belong to us. This is our moment. Indeed, this is one of the reasons why, after hemming and hawing, I finally decided to start writing on this more regularly.

Now, there is of course much wisdom about the timeless fundamentals of parenting which we should be taking from our Gen X/Baby Boomer predecessors. And certainly, we should never give in to the temptation to write Gen Z off tout court (remember when everyone was doing that to us?). I know some very offline Gen Z young adults who are kicking back against things, for instance.

But the fact is that we cannot reasonably expect guidance from previous generations on the unique challenges of the digital age. It’s not that they won’t give it to us, it’s that they can’t—so don’t blame them. Meanwhile, we have Gen Z parents coming up behind us who will want our advice. The oldest members of Gen Z are 27—by the time I was that age, I had a one-year-old.

So Millennial parents: this is our moment. Now is the time to work out and build those things which will help the generations after us to navigate a digital world which is here to stay. We have to write the books, to develop practices and habits, to set the tone, to create the resources. It’s our time—time to raise against the Machine.

So much of me wishes I could devote my parenting energies to something other than this—to something other than defending my children from an anti-human world. The constantly adversarial nature of it all can drive you to madness. Two things keep me sane in the midst of it.

First, remembering that need for a positive vision. Remember: we are raising. We have something higher, something True, Good, and Beautiful which we are, with God’s help, striving toward.

Second, accepting that, though the days are evil, they are the days God has seen fit to give us. All we can do is trust his providence and live by faith. Fortuitously, our family Bible reading today took us to Habakkuk 2:4 “the righteous shall live by faith.”

I will give the last word of this piece to Tolkien—a man all too familiar with the Machine:

“I wish it need not have happened in my time,” said Frodo.

“So do I,” said Gandalf, “and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”