Raise Against the Machine #3: Home, A Small Country

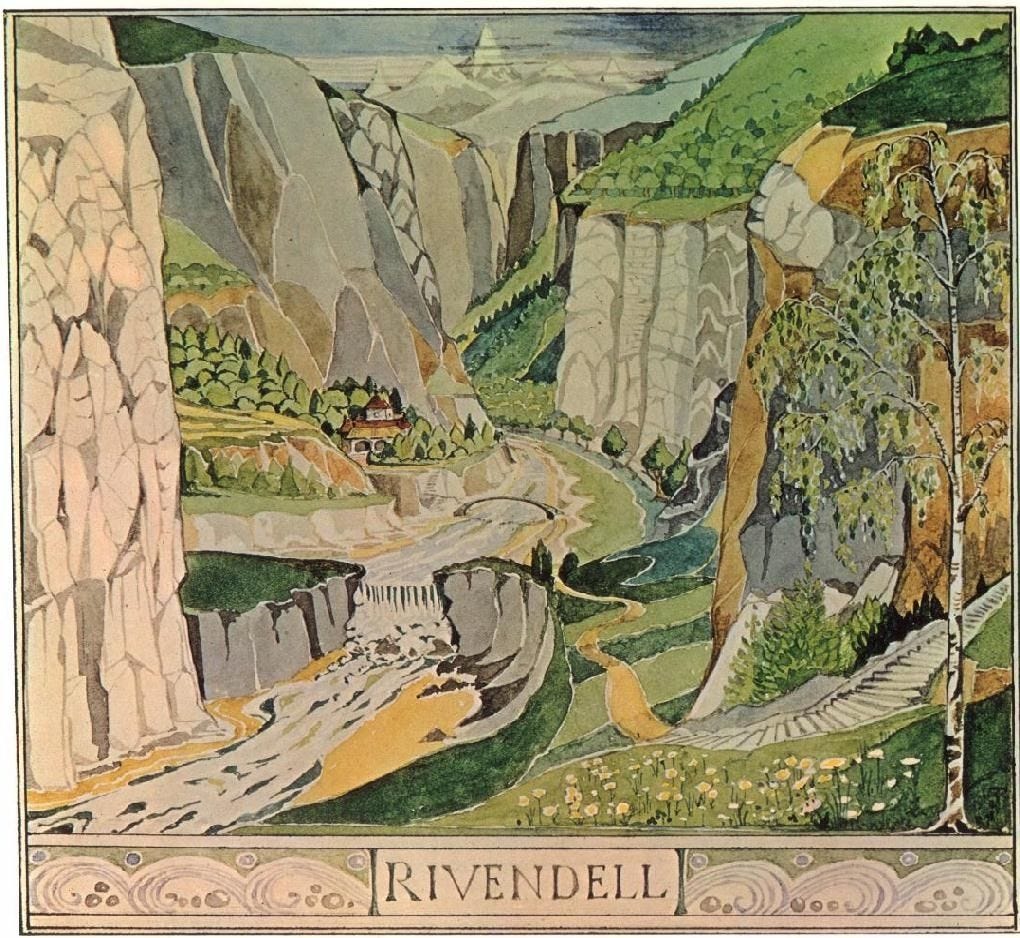

Thoughts on how to build Rivendells in space and time

Early on in our marriage, I asked my wife “what would you like our home to be like?” She thought for a moment, though only a few seconds—a woman who knew exactly what she wanted to say, but had never had to put it into words before.

“Like a small country”, she said.

As our family grows—we have three children right now—I think of those words often. They were a lightbulb moment for me. They’ve been particularly on my mind since I started this open-ended “Raise Against the Machine” series, trying to think out loud about how to raise a Christian family in the digital age. As I’ve stressed in the first two posts (here and here): without a positive vision, you’re doomed. You can’t just be “against”, but have to be raising up toward something. Thinking of home as a “small country” has been very formative for me in that regard.

A home being like a small country means a distinct character and a rich culture. That doesn’t mean other places are necessarily worse—they’re just not yours. A home like this will be a refuge in a world of trouble. It will be a place where, when its inhabitants return, they kiss the sand of the seashore. It will have enough in it to form and fill a person’s identity for the rest of their life. It will be able to say, with a joyful confidence, “thanks, but that’s not how we do things here.” And it will not be insular, but happy to stand on its own two feet on the world stage of other households, gladly receiving visitors and sending ambassadors on its business.

If I were laying down a few core principles for raising positively against the Machine, one would be this: make your home worth being in.

The first thing I thought of when my wife spoke of “a small country” was J.R.R. Tolkien’s descriptions of Rivendell in The Hobbit:

[Elrond’s] house was perfect, whether you liked food, or sleep, or work, or story-telling, or singing, or just sitting and thinking best, or a pleasant mixture of them all. Evil things did not come into that valley.

And likewise, in The Silmarillion:

In all the days of the Third Age, after the fall of Gil-galad, Master Elrond abode in Imladris [i.e. Rivendell], and he gathered there many Elves, and other folk of wisdom and power from among all the kindreds of Middle-earth, and he preserved through many lives of Men the memory of all that had been fair; and the house of Elrond was a refuge for the weary and the oppressed, and a treasury of good council and wise lore.

Rivendell is a place thoroughly worth being. All Christian homes should be Rivendells.

Food, sleep, work, story-telling, singing, just sitting and thinking, good council, wise lore—these are the things which make homes worth inhabiting. And, when you then leave the home—either as an emissary to some other household, whether friend or foe, or to establish a new colony over the horizon—you will be thoroughly worth having.

So much of modern life pushes us to be concerned with things outside of the home. Since the Industrial Revolution, the home has shifted from being a place of production to a place of consumption. The spheres of work and family have been thoroughly separated, and our homes have largely become aeroplane hangars, where disconnected individuals briefly dock for food, sleep, and the consumption of passive on-screen entertainment, before scattering themselves to the four winds once more.

For one of my Davenant Hall classes this term, I recently read a couple of chapters from Christopher Lasch’s 1997 book Women and the Common Life. At one point, Lasch quotes Benjamin Rush, a lesser-known American Founding Father, who wrote a great deal about education. In a 1787 tract, Thoughts on Female Education, Rush—writing in the early days of the Industrial Revolution and US republic—inveighed against the early signs of what I’ve just mentioned: the consumptive lifestyle which proliferates under modernity. Rush could see it appearing especially among the affluent women of the new American elite, who were essentially becoming useless coquettes in the style of those Old World aristocrats to which the Land of the Free was supposedly opposed. Rush compared these idle women to “a valuable mistress of a family” who industriously applies herself to the running of a household (which, in the 1780s, was not like being a 1950s housewife):

The business of the one, is pleasure, the pleasure of the other, is business. The one is admired abroad; the other is honoured and beloved at home.

Rush’s remarks are truer even now than they were then—both for men and for women. They put me in mind of a Wendell Berry line, which I know from Paul Kingsnorth’s essay “Learning What To Make Of It”:

Do you think it could be a general rule that the only place one is urgently needed is at home?

It’s good that Berry says “as a general rule.” One has other social obligations than the household—indeed, households have obligations beyond themselves. A household should never be entirely unto itself. Aristotle understood this centuries ago in his Politics:

Further, the state is by nature clearly prior to the family and to the individual, since the whole is of necessity prior to the part; for example, if the whole body be destroyed, there will be no foot or hand, except in an equivocal sense, as we might speak of a stone hand; for when destroyed the hand will be no better than that…. The proof that the state is a creation of nature and prior to the individual is that the individual, when isolated, is not self-sufficing; and therefore he is like a part in relation to the whole. But he who is unable to live in society, or who has no need because he is sufficient for himself, must be either a beast or a god: he is no part of a state.

It can raise the hackles of conservative Christians like me to see Aristotle saying the state is clearly “prior” to the individual and the family—we’re usually very keen to keep the state’s hands off or our household and personal rights. But I don’t think Aristotle is talking about absolute state priority over the family in the way that, say, communism imagines it. Rather, his point is that the individual and the family are not ends unto themselves. Their “final cause” lies beyond themselves, in a wider community of which they are a part. We all know this to be true in practice: healthy families create a healthy society, and a healthy society supports healthy families.

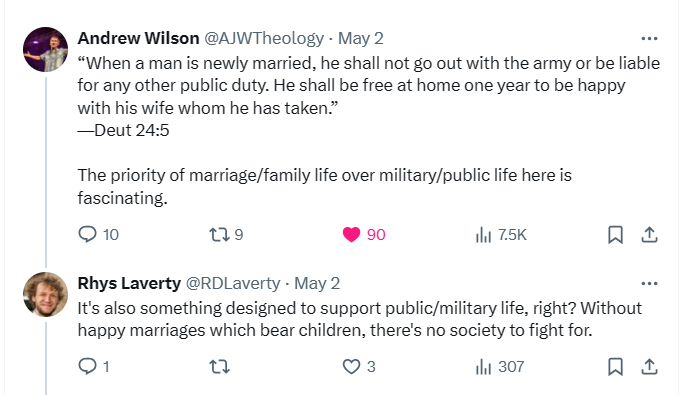

The biblical treatment of this dynamic cropped up in my roamings online this week, when, on Twitter, the excellent Andrew Wilson pointed out the importance that the Old Testament law gives to marriage relative to public and specifically military life. I chipped in with a thought to round out the picture:

All that is to say however: Berry’s instinct is right. We are urgently needed in our homes far more than we realise.

And yet strong forces are mustered against anyone who wants to meet that need and put real thought into the shape of their home. We live in a world in which we are encouraged to make pleasure our business, rather than to make the business of a productive home our pleasure. We are pushed to seek admiration abroad—either in our work, or by attempt to retain the life we had before parenthood—rather than being honoured and beloved at home.

How, then, does one fill a home with the things of Rivendell?

To give a brief, somewhat practical framework, we could break it down this way: think about space, and think about time.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The New Albion to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.