A Happy New Year to all my readers, and a warm welcome to you new readers who have subscribed in the last six weeks or so (which is quite a few of you—I’m not quite sure where you all came from, but very glad to have you)!

Usually, I post on The New Albion every week, but family trials and the Christmas break meant that writing has been squeezed out since early December. I usually only have a 2-3 hours per week maximum to write here, so it doesn’t take much to derail things. If you’d like to support me so I can reach a point where I can devote more time to this project, then why not consider a paid subscription?

This is a free public post to kick off 2024—roughly ¾ of posts are subscriber only.

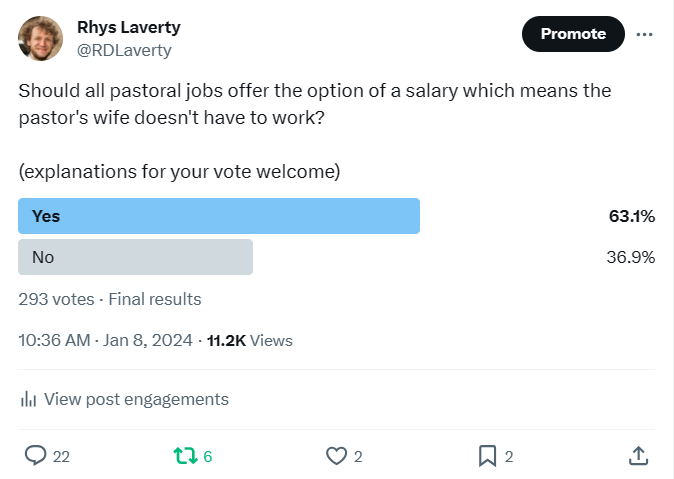

This week, I ran a Twitter poll. I asked whether all pastoral jobs should offer the option of a salary which means the pastor’s wife doesn’t have to work.

This was prompted by repeated conversations I’ve had with friends and peers in search of church ministry roles who find the salaries on offer wholly inadequate—especially if they are looking for a family wage to support the whole household. These are not men looking for an extravagant lifestyle—they simply want to be able to maintain a reasonable standard of living in the places in which they are called to minister whilst discharging their pastoral duties to the full.

Many evangelicals grew up with pastors whose wives didn’t work, and much evangelical pastoral ministry has long operated on this assumption. There’s a dark side to this of course: “pastor’s wife” can be a tough gig, full of unspoken assumptions and expectations. Yet even in churches blessedly free of that, it’s still been long assumed that the necessary burdens of pastoral ministry on the pastor’s home life (e.g. using his home for an above average amount of hospitality, an unpredictable schedule due to pastoral needs) are sufficient to make a family wage a reasonable part of the role.

Most evangelicals in my generation (i.e. Millennials—I’m 31) grew up seeing this model. Also, we have grown up hearing a huge amount about the need for “gospel workers” in the UK, and have been the first generation fully reared in the evangelical “church planting boom” inspired by the likes of Tim Keller. “The harvest is great, but the workers are few”, we have been told often. Yet now Millennials are beginning to come out of theological college, and it seems that, yes, the harvest is great but the workers are few… and yet the jobs are even fewer. And it seems they are expected to do those jobs in conditions which are quite alien to those who encouraged them into ministry and trained them for it. There is a prevailing sense among my peers that many pastoral salaries for jobs aimed at men in their 30s are set by men in their 50s and 60s who pay low mortgages and whose wives never worked, and who are essentially out of touch with the expense of family life in 2024.

Now, let me say at the outset: I know that, for many churches, being able to provide any pastoral wage at all is a struggle. I get that entirely, and I am not taking aim at churches who are doing their best to give sacrificially in order to support their beloved pastor. My concern is not with churches who are in such a situation; rather, it’s with what principles the conversation actually involves, even if for many it’s hypothetical.

To boil down my real question here: what are we actually talking about when we talk about a pastoral family wage?

Cards on the table: I think pastors have a right to a family wage, and so providing one should be high on a church’s priority list. In short, I find it hard to read 1 Corinthians 9 in any other way that does justice to both its context and ours. A growing number of people, however, would disagree with me. I was pleasantly surprised to find that 63% of responses to my (entirely unscientific) poll agreed, yet I imagine if I’d run the poll 30 years ago then the percentage would have been even higher. And even among those who expressed agreement, there seemed to me a sense that a family wage is something which “would be nice” if possible, but isn’t a priority.

This is where my interest is piqued, and where I want to try and scratch out something I sense is missing in UK evangelical thinking.

What We Talk About When We Talk About the Family Wage

I sense that the main source of reservations regarding a family pastoral wage is that such a wage would simply be out of step with how most people live today. Economic conditions now mean that it is often harder for churches to fund such a wage, and that fewer church members would have a similar lifestyle. Fewer and fewer people are able to survive on one person’s (usually the husband’s) salary, so why should we expect pastors to be any different? What’s more, given people are now more financially stretched, it’s simply harder to raise the money for a pastoral family wage through church tithes. And so, although it would obviously be “nice” if you could, paying a pastoral wage just can’t be done a lot of the time, and so we should crack on with what we have.

I fear, however, that such an assessment far too quickly brushes over the significance of those changing economic conditions.

The death of the single-income family is not simply an economic fact. It is a social one—and an enormous one at that, with some significant moral implications. Even if we can do little about it, its demise should not simply be shrugged at.

The single-income family is, it must be noted, a very modern phenomenon—largely post-WW2. It has already apparently expired. And to the extent that its advent was tied to the modern turn from households as sites of productive communal labour to sites of recreational individual consumption, it is far from ideal. For most of human history, both husband and wife (and, as soon as was feasible, the children) contributed to the household economy. But for all that it lost by creating “the housewife”, the single-income model preserved some important elements of its predecessors: notably, it allowed mothers to continue devoting significant time to childrearing. In earlier times, the family may have all been working but they were generally working as a family (and usually in a wider familial network than the nuclear family).

The increasing impossibility of a single-income family has driven many women into the workplace in recent decades. Feminists dress this up as the empowerment of women; in reality, much of it is simply economic necessity. Stats persistently show that c.20% of mothers want to be full-time stay-at-home-mums, c.20% want to be something like “career women”, and the middle 60% are somewhere in between—though it seems reasonable to assume that a good number of that 60% would happily stay at home full-time for a season, whilst their children are young. Our vision of this is skewed, because the kinds of women who we hear from in the public square (e.g. Labour MP Stella Creasy, who complained over Christmas about the “motherhood penalty” incurred by having to spend time with her children) tend to be the careerist 20%, who think they speak for all women.

There has recently been a notable turn among some non-Christian thinkers acknowledging that, actually, a system which allows mothers to remain at home during their children’s younger years is beneficial for everyone. Making this impossible makes women miserable and hinders child development (and probably isn’t great for men either). Louise Perry (author of The Case Against the Sexual Revolution and hostess of the Maiden, Mother, Matriarch podcast) and Mary Harrington (author of Feminism Against Progress and the Reactionary Feminist Substack) are at the forefront of this, and eminently worthy of your attention.

I don’t have the space here to sketch out a full Christian case for supporting an economic model which allows mothers to devote a large amount of time to childrearing, but suffice to say that it has been a common sense assumption for most of humanity throughout history and I think it’s quite simply assumed by the Bible as part of God’s obvious design for humanity. To caveat myself again: I do not think this is the same as being a demure 1950s housewife.

So a “family wage” is not simply something which is “nice if possible”. It was, in fact, one of the last bulwarks holding up a core element of God-given natural family life which is essential for human flourishing. And its demise is demonstrably damaging to the fabric of society.

For one thing, it is directly linked to declining birth rates, and our coming demographic collapse: if it’s impossible to support a family properly, people will either not have one or have smaller ones. But this is sending us into oblivion. Developed countries need 2.1 women per child to maintain their population size; in the UK, we have 1.58. Admittedly, UK fertility has been tanking since the 1870s, but its biggest revival since then was in the post-WW2 era when the single-income family was a common reality.

For another thing, when we do have children, they are now driven into nursery care at increasingly young ages. Labour are mooting the possibility of expanding childcare availability from the age of six months. This is dressed up to sound like “providing options”, but it should be obvious to us by now that, once this is introduced, it will morph into the norm and soon our economy won’t be able to function without it, and in a generation we will be forcing mothers to abandon their six month olds or face poverty (we have a six month old—it’s only at this age that they start to be lots of fun!). UK stay-at-home mums have already been shamed for being “economically inactive” by a supposedly Conservative government—I shudder to think what Labour will do.

The problems with mass childcare are myriad. They range from the apparently mundane (exhausted children, the erosion of sibling relationships), to the fairly concerning (normalisation of screens in schools and nurseries, anxiety, bullying, academic pressure, LGBT ideology), to the downright big-picture alarming (see, for example, Mary Harrington’s convincing speculation that being raised by risk-averse nursery maids is partly to blame for the Millennial/Gen Z desire for more totalitarian forms of government).

It has fallen to non-Christian voices to begin making noise about this. Perhaps, in the end, nothing can be done about it—the problems are too big. But at least they will have tried. British evangelicals, on the other hand, seem to have nothing to say about this issue even at the level of principle. Our response to the loss of the pastoral family wage is largely “yes, it’s a shame” rather than sounding the alarm on the major social issues of which it is a symptom.

When it comes to paying our pastors, evangelicals are very aware of the biblical injunction to not muzzle the ox when it is treading out the grain (1 Cor. 9:9; 1 Tim. 5:18). But in an economy of inflated prices and depreciated wages, we’re all muzzled oxen now. Yet the dual income economy has been so normalised that we no longer see this for the scandal it is—even if it is one that is impossible to change. When it comes to teaching on work, money, and family, if evangelicals are doing their contextualisation properly, we should basically be telling most people “you are being royally shafted.”

A Question of Priorities

And so, if we accept that the death of the family wage amounts to an economic shafting (dare I say “injustice”?) of British families, we are then faced with this question: do you shaft pastors in the same way if it’s at all possible to do otherwise?

There are, of course, perfectly good reasons for a pastor to have a sub-family wage. As numerous people pointed out in response to my poll, if we said “family wage or bust!” then lots of churches wouldn’t have a pastor at all. Church planters, pastors in deprived areas, small churches—these are all understandable scenarios for a sub-family wage. I am sure that, usually, it is better to have some kind of pastor than none at all.

But my question about avoiding this if at all possible involves asking questions about priorities. How important is a pastoral family wage? All situations will be different, but let’s throw out a hypothetical: a 5 year old evangelical church plant has been paying its pastor a modest wage, but his wife has had to work as well to make this possible, and their young children are in primary school and nursery. After steady growth, the church has some additional funds. In a typical evangelical church, the next natural move would probably be to possibly hire an Associate Pastor or a Youth and Children’s Worker. How many churches would consider using those funds to pay their Senior Pastor a substantially increased wage to remove strain on his family life and allow him to be more effective in ministry, as well as be further honoured for the work he already does?

I think most UK evangelicals would baulk at this idea. For one thing, as noted above, we tend to jump at anything that “multiplies Gospel workers”. I think plenty (most?) would argue that two modestly paid ministry staff is better than one well paid one.

For another thing, I think we instinctively recoil at the idea of increasing the Senior Pastor’s wage in the above scenario, as it seems like “doubling up”. “He’s already being paid an average salary and isn’t starving”, we say; “why should we effectively pay him two salaries?” His existing salary is seen to be honour enough. Increasing it substantially would amount to some sort of grotesque double honour (see 1 Timothy 5:17, if you’ve not caught my drift here).

If evangelicals can accept the scandal of an economy which forces both parents out of the home, then we need to ask how comfortable we are to facilitate that scandal in one of the few places where we do (possibly) have the ability to make an economic difference: our pastoral salaries.

The Rise of the “Staff Team”

This all touches on another potentially sensitive subject which I’ve seen little addressed: the advent of “the staff team” in evangelical churches.

In this discussion, many who are iffy about prioritising a pastoral family wage point out how much has changed since, say, 40 years ago. And they’re right, as I’ve noted: our economic conditions are terrible. Yet something else that was different 40 years ago was that very few evangelical churches had a “staff team” consisting of both pastoral staff and admin/support staff. Although there are still plenty of churches which barely scrape by with one pastor, the “staff team” model is increasingly common in medium-to-large UK evangelical churches. Most evangelicals probably have a pretty instinctive idea of how such a team should grow as time goes on: Senior Pastor, followed by Associate or Youth Pastor, followed by Women’s Worker, followed by Church Administrator, followed by etc etc.

I’m sure much that has led to our current “staff team” culture is good and wise. I have heard plenty of horror stories of the old “one-man ministry” model so common in the past, especially in the nonconformist free church background in which I have been raised. And it is true that the harvest is great but the workers are few, and so we should pray for the Lord of the harvest to raise up workers for the harvest field (Matt. 9:37-38). The growing prevalence of larger staff teams in evangelical churches is, undoubtedly, in part an answer to people who have prayed this prayer in recent decades.

And yet. We should be willing to question why we have allowed the advent of the “church staff team” to run in parallel with the ongoing death of the family wage. In churches capable of having a staff team, the issue is clearly not cashflow as such, but a question of priorities. Is it really always or usually better to have a few modestly paid pastoral staff and administrators, or one or two well paid ones? If you think so, is it because the very idea of paying a larger family wage to one pastor is a scandal in our current climate? If so, how is that consistent with the idea of giving him “double honour”?

I’m not saying there aren’t good answers to those questions. But I have not seen them much addressed in view of the issues we’re discussing here, so would welcome comment on them.

And another, possibly provocative note: you’d be hard pressed to find anyone who’d argue that evangelical ministry has become less managerial in recent decades. Unavoidably, churches will always take on prevailing cultural assumptions about working life. It is increasingly acknowledged that central institutions in society—the government, the civil service, Big Tech companies—suffer from “administrative bloat”. We should be able to ask whether this trend has affected evangelical churches.

Rights and Wrongs

A final concern to address is that of possible tension caused by paying a pastoral family wage. As noted, supporting a family on one salary is now unobtainable for many. Pastors, it is generally felt, should live in a way fairly in-step with their local community. And so the thinking goes that paying a pastor a family wage, when this is unobtainable for his peers, will cause trouble.

I do think this is a valid concern. Pastors do, I believe, have a right to demand a family wage. In part this is simply because I think everyone should be able to support their family in a way that allows mothers to spend a large amount of time at home. I think 1 Corinthians 9:4-6 are also fairly clear on this point:

Don’t we have the right to food and drink? Don’t we have the right to take a believing wife along with us, as do the other apostles and the Lord’s brothers and Cephas? Or is it only I and Barnabas who lack the right to not work for a living?

This seems fairly clear cut to me: Paul thinks pastors have the right to enough money to feed themselves, support their families, and to not have to work for a living (which surely includes his wife, too). v14 is even clearer: “The Lord has commanded that those who preach the gospel should receive their living from the gospel.”

Yet, of course, Paul says this in the midst of explaining how he willingly gave up his rights for the sake of the Gospel: “If others have this right of support from you, shouldn’t we have it all the more? But we did not use this right. On the contrary, we put up with anything rather than hinder the Gospel of Christ” (9:12). He did this so that he could win a hearing among the largely pagan Corinthians and (it seems fair to assume) maintain that hearing among them once they joined the church.

And so pastors are certainly free to deny themselves their rights for the sake of the Gospel. This is one of their callings and burdens. But the aspiration of churches should be to be generous, to honour (doubly!) the pastor’s rights, and to cultivate a spirit among their people which does not baulk at doing such things. 1 Corinthians is an epistle largely prompted by the spiritual immaturity of the Corinthians, and is the locus classicus for dealing with those “weaker brothers” who struggle with things which are permissible—whether that be eating food sacrificed to idols or paying your pastor a sensible wage. The book teaches us that there will be times where we must gladly concede to the sensitivities of weaker brethren, yet I cannot imagine that any sensible exegete of the book would think that we should be content to let people remain in those sensitivities. The goal is always maturity, attaining to the whole measure of the fullness of Christ (Eph. 4:13).

Consider an alternative example: if a church largely made up of people who earn minimum wage or live on benefits committed to pay its cleaner the Living Wage, and they experienced pushback from the congregation, what would be an appropriate pastoral response? Context would differ of course, but I imagine that most church leaders would go out to bat for this, and defend the decision as a matter of justice. So why not do the same with defending a pastoral family wage?

If your main concern with a pastoral family wage is the disparity this would cause between the pastor and the congregation, then it’s quite possible that you need to aspire to cultivate a stronger conscience in your church members. It seems to me that much opposition to pastoral family wage amounts to saying “we are happy to let our people behave like the Corinthians”, which I doubt is a place where anybody who has studied 1 Corinthians wants to leave anybody.

Concluding Thoughts

My intent here has not been to cast aspersions on the sacrificial and strategic financial decisions that many UK evangelicals churches and their pastors have made in working out salary arrangements. I am on record talking about how I think that evangelicalism, right now, is where God is excitingly at work in the Western church.

Rather, my intent has been that of The New Albion as a whole: to bring an awareness of current UK cultural issues to bear upon conservative evangelical thinking, and to encourage deeper thought on these issues within the constituency I call home. I may be highly mistaken in some of the judgements or suggestions I’ve made above—I am very open to pushback (and I have made comments open to everyone below). The questions I’ve posed above aren’t rhetorical, but sincere and offered in good faith. I confess I have never been in a position to make these financial decisions in a church setting. If I have unduly ruffled feathers, then I apologise. But, in all the evangelical resources I have found regarding pastoral salaries, I have seen next to no consideration of the bigger social issues which seem most pertinent to the question. This seems too important not to discuss.

My concern, really, is not with pastoral wages at all, but with evangelical awareness of the powerful undercurrents in our society which are destroying family life and the wider social fabric with it. If it were apparent that evangelicals have stared down the barrel of the sorry state of family life in the UK in 2024, then we’d be having a different conversation. But I fear we have yet to do so.

So, so good. You touch on all the needed points in this conversation (big fan of Mary H. and Louise P. ...as well as a bit of a fertility demographic and family policy nerd.)

I've often thought about this topic, based on the pastors and their families I've encountered — but have never seen anyone write point-blank about it. As someone who's concerned about the all around strain on family formation and family health in this two-incomes-often-necessary economy (here in the US, too, in major cities), I really appreciated this.

I am able to stay home with our 3 small children, and honestly it would be a bit devastating if I had to be away from them 40+ hours a week. Women certainly have options to do that! (The Industrial Revolution obviously changed the nature of work... but raising young children nearer to home with one parent—or two in a more creatively flexible way—is the best we can do sometimes, in the absence of familial home economies!) So allowing mothers that natural option to be with their kids is definitely worth fighting for. No less for our own pastor's family.

Thanks for writing this.

Thanks. From the point of view of the Pastor's salary, this was most opportune as we were discussing our budget after church on Sunday. For a small, relatively new church, his salary, a working one, takes up 1/3rd of the budget plus we have a considerable shortfall but enough savings to last another year.

I agree that we should be paying a working wage, from scripture plus I think there is enough in people's pockets to meet all this. The worker is worth his due and the work is there.