O here it is!

And there it is!

And no-one knows whose share it is

Nor dares to stake a claim;

But we have seen it in the air

A fairy — like a William pear

With but itself to blame.

A thug it is!

And smug it is!

And like a floating pug it is!

Above the orchard trees

It has no right — no right at all

To soar above the orchard wall

With chilblains on its knees!

This is a favourite poem in our house right now. Specifically, my wife’s favourite. We try to read some poetry aloud most days at the family dinner table. As far as we can tell, this little ditty is anonymous. We found it in an anthology of similar poems we picked up second-hand somewhere—that is, nonsense poems.

We’ve grown to love nonsense poetry in our house. Lewis Caroll, Ogden Nash, and plenty of Edward Lear. Nonsense is a wonderful place to introduce poetry to children; not because it is silly, but because good nonsense poetry is about sheer joy in language, in the words themselves, their jump and jangle. This is true of all poetry of course—poetry is language under pressure. But it is particularly true of nonsense poetry. A poorly chosen phrase can make a poem fall flat, but if it’s a nonsense poem it falls even flatter. Lewis Caroll’s “The Walrus and the Carpenter” shouldn’t work, and yet it does, because Carroll brings all these absurd, dissonant words into an accord that, somehow, he discerned in the ether.

I will confess that, sometimes (and only sometimes, and only very, very briefly) in our snatches of after dinner nonsense, I feel like one of Plato’s imagined philosopher-kings. In Plato’s Republic, the philosopher-kings are afforded leisure—scholē in the Greek, the root for “school” and “scholar”, if you can believe it. Leisure isn’t idleness. Rather, it’s the time and space to contemplate, to develop wisdom, and to consider things in themselves. Leisure is a date with Reality, a chance to be romanced by Lady Wisdom.

In fact, more than feeling like a philosopher-king, I feel… Bombadilish.

Tom Bombadil, the most mysterious of J.R.R Tolkien’s creations, comes lolloping into The Fellowship of the Ring singing nonsense:

“Suddenly he stopped. There was an answer, or so he thought; but it seemed to come from behind him, away down the path further back in the Forest. He turned round and listened, and soon there could be no doubt: someone was singing; a deep glad voice was singing carelessly and happily, but it was singing nonsense:

Hey dol! Merry dol! Ring a dong dillo!

Ring a rong! Hop along! Fal lal the willow!

Tom Bom, jolly Tom, Tom Bombadillo!— from The Fellowship of the Ring by J.R.R Tolkien

There are always so many questions about Tom Bombadil, for both fairweather fans and hardcore Tolkien nerds. Is he an angelic Maia? An unfallen man? A symbol of nature? Eru Ilúvatar himself? I’m not going over that old ground today. With impeccable timing, David Rowe noted on Twitter this week that people are so often looking “through” Tom Bombadil to find out what he “really” is or what he represents, rather than simply looking “at” him and remembering that he is simply Tom Bombadil. It’s as his wife Goldberry says when Frodo asks: “He is”.

I’ll indulge one question today though: why does Tom Bombadil sing nonsense?

I asked this to myself whilst my wife and I were hate-watching Amazon’s Rings of Power last week. I truly tried to keep an open mind about Rings of Power when it first broadcast last year. Sadly, my Hyde-like cynicism was vindicated over my Jekyllish suspension of judgement. It was as bad as I imagined and worse (though I do seem to end up occasionally defending bits of it against my wife, who is even more incensed by it than I am).

Returning for the show’s second season, which is currently broadcasting, I tried to hold out hope for one aspect: the appearance of Tom Bombadil, played by Rory Kinnear. I was surprised by the casting—in my imagination, Bombadil looks a touch older and more rotund. But, Kinnear is a top-tier British Shakespearen actor, so I hoped for the best.

Unfortunately, Hyde won again. The writers could have not given us a more poorly understood version of Bombadil if they had tried.

The most striking thing about Bombadil in Fellowship is his indifference to both the Ring and the fellowship’s quest to destroy it. When he encounters the hobbits, he tosses the Ring in the air without a thought, peers through it, laughs, and is immune to its power of invisibility. When it’s suggested by Elrond that he should have been invited to the Council, Gandalf gruffly states that he would not have come, and that even if he were to take the Ring at the behest of all the free people of Middle Earth he would not see the need to destroy it. He would either forget it or throw it away.

The Bombadil of the Rings of Power, however, seems full of earnest concern for the events transpiring in the outside world. Speaking of the series’ mysterious Dark Wizard, he talks of how the Wizard will combine with Sauron and “there will be no end to burnin’ till all Middle-earth is ashes.” True, Bombadil then declines to get directly involved, saying he will instead gather lilies, but he then rather grandly tells the Stranger (widely assumed to be a younger, yet-to-be-named Gandalf) that it is his task to stop the forces of evil.

This is a very hard portrayal of Bombadil to swallow. If Tom cared not a jot for the One Ring when he held it in his very hand, it is hard to imagine him furrowing his brow over the wranglings of wizards centuries earlier.

Now, there may be a nerdy argument to be made in defence of this portrayal. We know Tolkien’s Bombadil wandered Middle Earth for a long time, seeing a great deal along the way, and being spotted enough to enter the tales of both Elves, Dwarves, Men, and Hobbits. Perhaps Rings of Power could claim to be giving us an earlier Bombadil, more concerned with world affairs before he confined himself to his modest domain just east of the Shire.

But I just don’t buy it. Most likely, Amazon wanted to cram in as many known Tolkien characters as they could to market the series, and had to find a way to make Bombadil useful.

Returning to our question: it was in the midst of grouchily hate-watching all this with my wife last week that I asked myself “why does Bombadil sing nonsense?” Rory Kinnear’s Bombadil was certainly muttering nonsense songs to himself, but it was hardly the “deep and glad voice” bellowing out “hey dol, merry dol!” that Tolkien writes of.

Despite all the ambiguities about what he is, Tolkien does actually say a fair bit about Bombadil’s function. One example:

But Tom Bombadil is just as he is. Just an odd ‘fact’ of that world. He won’t be explained, because as long as you are (as in this tale you are meant to be) concentrated on the Ring, he is inexplicable. But he’s there – a reminder of the truth (as I see it) that the world is so large and manifold that if you take one facet and fix your mind and heart on it, there is always something that does not come in to that story/argument/approach, and seems to belong to a larger story. But of course in another way, not that of pure story-making, Bombadil is a deliberate contrast to the Elves who are artists. But B. does not want to make, alter, devise, or control anything: just to observe and take joy in contemplating the things that are not himself. The spirit of the [this earth] made aware of itself. He is more like science (utterly free from technological blemish) and history than art. He represents the complete fearlessness of that spirit when we can catch a little of it. (emphasis mine)

“Just to observe and take joy in contemplating the things that are not himself.” Bombadil revels. He is the philosopher-king of the Withywindle, growing in wisdom as he knows each tree and acorn and loving that wisdom as he goes.

And this is why I think it makes sense that Bombadil sings nonsense. Good nonsense poems are sheer love of words and how they sound together, regardless of what they’re about. It requires a loss of self-consciousness—otherwise, you feel too silly reciting it. But if you can take your eyes off yourself, and simply love the words—just like Bombadil’s eyes are off of himself and on each nook and cranny of his corner of the Old Forest—then there are few things more joyful than rattling off “The Owl and the Pussycat.”

And this is why Bombadil is so uninterested in the great sagas of Middle Earth that the rest of us find so absorbing. He is utterly ahistorical. Toward the end of Return of the King, after all the world-shattering heroics of the trilogy, Gandalf comments that Bombadil is “not much interested in anything that we have done and seen.” Harold Macmillan supposedly once said that “events, dear boy, events!” are what knock a government off course, a line often applied to the unpredictability and excitement of history in general. Events are precisely what Bombadil is not interested in. For him it is not events, but “things, dear boy, things!”

With all this in mind, I have wondered if there is any more significance to Rings of Power’s portrayal of Bombadil than just an Amazon cash-in. The fact is that a true portrayal of Bombadil would be utterly uninteresting on screen not only because he wouldn’t advance the narrative, but because his nature is arguably more incomprehensible to us now than it has ever been.

To simply delight in a thing in itself is only possible when that thing is received as a gift. And in the secular frame, nothing is a gift, because there is no divine Giver. Indeed, there really are no things—just the indifferent leftovers of matter being pushed around the plate of the universe. And so things must be given significance by being pressed into some narrative, which itself has been dreamt up and forced upon reality by a world grieving the death of God and the loss of the Christian story. I remember a friend of mine, a Christian who teaches in a secular university, telling me how, tongue-in-cheek, he once encouraged a professing hardcore Communist undergraduate student to walk the walk instead of just talking the talk. He asked the student, “If Jesus isn’t coming, and you’ve got to build heaven on earth, then what are you waiting for?”

The Christian can rest assured that, ultimately, the Author of reality will conclude his story, and so can rest easy in Bombadilish joy and contemplation of things themselves. But the secularist cannot do so for long without getting itchy feet. For them, the Story won’t write itself. It is a profound irony that materialism leads to the inability to truly enjoy Things.

This then, I think, is why Rings of Power’s Bombadil has been swiftly frogmarched into something so tedious as a plot. As the self-elected Authors of the story of reality, it would irk us to encounter a true Bombadil, to encounter someone utterly uninterested in our great quests and cataclysmic deeds.

Occasionally, we do encounter Bombadils in real life. My wife and I have noted a few people who are not unlike Old Tom as we’ve discussed all this over the past week. By nature, such people actually get on my nerves. When I wish to talk about Important Matters, they are absorbed, like a child, in a moth that has settled on the table or on the grooves of a man made hill in the distance.

But time has made me more Bombadilish, I am glad to say—less interested in events, events, and more inclined to enjoy Things, Things, and much happier than ever to sing nonsense.

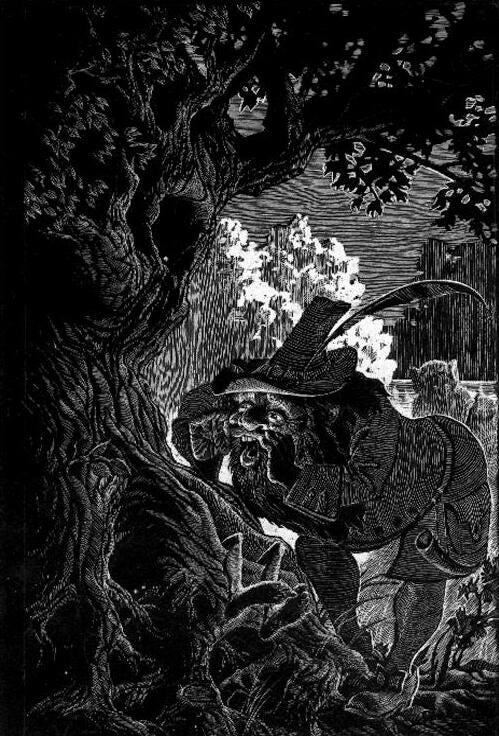

*Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

A joyful read!